Horny Jew

So, what's with the horns on Michaelangelo's Moses? An ancient European anti-Semitic slur? A mistake, the result of reading the Bible incorrectly? Neither, in my opinion. This is simply the result of being heir to a tradition that does not centralise the Masoretic text of the Bible. To explain:

There are lots of Bibles. Even if we assume that there had once been such a thing as an 'original' Bible, there ended up being many developments from it. In the 3rd century BCE the Pentateuch was translated into Greek, producing several Greek versions; the Greek was translated several times into Latin, producing different versions there; by the 2nd century CE, the Hebrew was again translated into Syriac and, at some stage, into a variety of Aramaic translations; by the 5th century CE, the Hebrew was translated directly into Latin. Then there are all of the further translations into Coptic, Ethoipian, Armenian, English, German, etc. Many of these translations are, themselves, made from translations and not the 'original' text. In fact, even the Hebrew today does not represent an original for a very simple reason.

In putting together the standard text of the Hebrew Bible, 9th century CE scholars in Tiberias (known as the Masoretes) chose readings based on majority texts. To put it simply, if there were two Hebrew manuscripts with a particular reading and three with a different one, then they would side in favour of the three scrolls over the two. That's all well and good, but it means that they ended up with a text that does not represent any ancient text. It's a conglomerate. A text designed by a committee. And it's known as the Masoretic text.

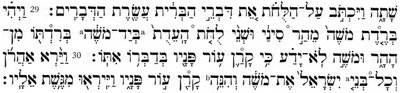

Now, the Masoretic text (or MT) also features something that previous Biblical texts lacked: a system of vocalisation and punctuation known as the מסרה (Masorah, 'tradition'). This was a purely Tiberian development (although there were cognate developments in both Southern Palestine and Babylonia). I mentioned in the previous post that such vocalisation can also serve a disambiguating role. Let's have a look at Exodus 34:29-30:

My translation:

29. And when Moses was coming down from Mt. Sinai, the tablets of testimony were in Moses' hand during his descent down the mountain. But Moses did not know that קרן עור פניו from having spoken to Him.

30. Aharon and all the Israelites saw Moses, and look! קרן עור פניו! And they were too scared to draw close to him.

It is obvious that an understanding of the passage (which continues in v33 with Moses needing to cover his face before speaking to people) depends upon an understanding of the clause קרן עור פניו. What was it that happened to Moses' face? Let's look at each word in turn.

קרן is a word meaning 'protuberance', but is here vocalised as a verb - 'he/it protruded'. (Verb. √קרן Qal 3ms perfective)

עור is a word meaning 'flesh'. (Noun m.sg. Either const. or abs. See discussion below)

פניו is a word, פנים, meaning 'face'. It is followed by the 3rd person masculine singular pronominal suffix: 'his face'.

(Noun m.pl.abs. - pl. in form but sg. in meaning, it sometimes takes a sg., sometimes a pl., verb - cf: GKC §145h)

In English, one of the ways that we express the genitive case is with the word 'of'. The hand of the king, for example. Hebrew, on the other hand, utilises what's known as the construct chain. Sometimes (generally, with singular masculine nouns or plural feminine nouns) the noun itself does not change. Hand is יד and the king is המלך. Hand of the king is simply יד המלך. Of course, 'hand' is actually a feminine word, but I refer here to the form rather than the meaning. A word which is feminine in form (say, מלכה - 'queen') will change its form if it is in a construct chain. Queen (מלכה) of the land (הארץ) becomes מלכת הארץ and the ה changes to a ת. So too with masculine plurals (such as בנים - 'sons'): the ם drops away altogether and leaves us with clauses like בני המלך, the sons of the king.

The confusion in verses 29 and 30 rests on this issue. Does the word עור ('flesh') serve as the object of the verb קרן ('it protruded')? Or is it in construct with the word פניו ('his face')? The truth is, from a purely consonantal reading of the text, we don't know. Because עור is a singular masculine word, it could actually be either: the form wouldn't change to alert us. What is the difference in meaning? Well, let's look at what the Masoretic scholars did with the text and we'll see.

In both instances, they've placed what's known as a disjunctive accent under the word קרן. The two accents are different from each other, but they are both equally disjunctive: they both separate that word from the words following (much like a comma in English). In other words, they don't want us to see עור as the object of the verb. Under the word עור (both times), they have placed a conjunctive accent - indicating that we are to read the word עור as being in a construct chain with פניו. The meaning:

It protruded: the flesh of his face OR (as it is traditionally read) "The flesh of his face radiated". Moses, in speaking with God, began to shine from the pores of his skin and his appearance was so blinding that people feared to draw close to him unless he covered himself up.

That's great, but what's the alternative? What happens if we read עור as the object of the verb instead, and פניו as the sole subject?

"His face protruded flesh". Pretty different, hey? So, it seems, that Michaelangelo was neither an anti-Semite (necessarily) nor incapable of reading Hebrew (again: necessarily). Instead, he was simply heir to a different and equally valid reading tradition.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home