The Omer: Why Do We Mourn? - part II

This post continues on from this one.

What then ensues, after this brief passage, is a lengthy description of Hadrian's seige, and a long-winded depiction of the seige's aftermath. This depiction is both grisly and exaggerated (making a claim that 800 million people were killed). I reproduce part of it here:

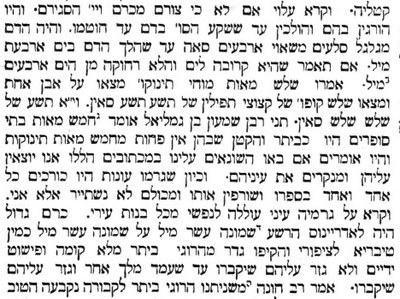

pTa'an 69a

pTa'an 69aThe following is the translation of Peter Schafer, The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World (London: Routledge, 1995), p158 - emphasis and parentheses are all his:

They [= the Romans] continued to slay them [= the inhabitants of Bethar] until the horses sank up to their nostrils in blood. And the blood rolled boulders weighing forty seah [forwards] until [after] four miles it reached the sea...

They said: The brains of three hundred small children were found on one rock. [Likewise] three baskets were found containing phylacteries [with a capacity] of nine seah each. Others say: Nine [baskets with a capacity] of three seah each.

It is taught: Rabban Shimon b. Gamaliel says: There were five hundred schools in Bethar, and in the smallest of them were not less than five hundred children. They used to say: If the enemy comes upon us, we shall go out to meet them with these pencils and bore out their eyes. When however sin caused this to happen, [the Romans] wound every one of them in his own scroll and burnt him...

Hadrian the blsphemer had a great vineyard of eighteen square miles, as much as the distance from Tiberias to Sepphoris. He surrounded it with a fence made from those slain at Bethar as high as a man with outstretched arms. And he commanded that they were not to be buried until another king arose and ordered their burial.

Can we learn history from this story? Not entirely, but there is also corroboration to be found in other sources. The midrash, Genesis Rabba (64:10), speaks of the revolt under Hadrian (although it does not name Shimon bar Kosiba) and the Tosefta (Shabbat 16:6) speaks of bar Kosiba but does not mention the revolt in which he participated. Sources that mention both are, unfortunately, scanty within the Jewish tradition.

There are Roman sources for the revolt, such as (Pseudo-)Spartianus and Dio Cassius - the latter mentioning bar Kosiba as well - and Christian historians Eusebius and Justin also relate their version of the events. It would be impossible to know anything for certain were it not for a few remarkable archaeological discoveries.

Coins issued by bar Kosiba's followers testify to his real name - in opposition to the bar Kochba of Rabbi Akiva, the bar Koziva of his detractors, and the Barchochebas of the Christian historians. They would also seem to indicate that, even if only briefly, his role of deliverer was somewhat promising. Leasehold agreements from Wadi Muraba'at use the formula, 'In the x-year of the Redemption of Israel by Shimon bar Kosiba, the Nasi of Israel', and the coins address their hero with the same term. What is more, collections of the man's letters have been found in Nahal Hever, testifying to the existence of his rebellion as well.

The language employed in these sources raises eyebrows. It is easy to see the tendentious nature of the Roman, Jewish and Christian sources (the last of which have bar Kosiba forcing Christians to renounce their Lord), but we must also learn to read between the lines of bar Kosiba's texts themselves. References to the liberation of Jerusalem (as found on some of the coins) do not necessarily indicate that he had been successful in liberating that particular city, and the despotic tone within his letters belie a great general's true success.

However bitter-sweet the all-too-brief moment of victory may have been, history has demonstrated to us its tragic end. The death of bar Kosiba himself was but a small thing compared to the destruction that ensued after his rebellion, and the overall catastrophe serves as a lens through which to understand the two Talmudic takes. The Palestinian Talmud, not content with grossly over-exaggerting the scale of the rebellion and its aftermath, reduces itself to snide name-calling and dubs the architect of the revolution a "liar". The Babylonian Talmud's response is somewhat more breathtaking.

Rather than reading the story of Rabbi Akiva's disciples as history, we should read it as what it truly is: a deep grief that can find no better expression than to completely eradicate bar Kosiba and his fateful insurrection from the annals of history. However moving this Talmudic response to crisis is, let us not perpetuate the Babylonian lie. Let us not condemn so many thousands of people to a second death every year by mourning their passing for an incorrect reason. And let us honour the memory of Rabbi Akiva, not by making him the mythological leader of a non-existent 24,000 disciples, but a true disciple himself. And one who did not mind declaring his allegiance in the face of widespread Rabbinic antagonism.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home